Modi: Not in the Seventh Heaven

Amulya Ganguli

Narendra Modi’s seventh year in power hasn’t been what he must have wanted. For one, the pandemic has eroded his image as an administrator. Even if the devastating disease is once-in-a-century occurrence, it has still brought out his inadequacies with regard to marshalling the country’s resources to meet the challenge.

For another, the year saw his party, the BJP, lose three of the four state assembly elections in West Bengal, Kerala and Tamil Nadu and stay ahead of its opponents in Assam by less than one percentage point – 44.4 against 43.5. As a result of these setbacks and because of the medical emergency caused by Covid-19, there are doubts as to whether the BJP will have an easy run in U.P., which the party regards as its stronghold under the ideologically hawkish chief minister, Yogi Adityanath.

The BJP’s doubts could not but have become deeper because of the gains made by the Samajwadi Party and the Rashtriya Lok Dal (RLD) in the recent panchayat polls in the state. The entry into the BJP of a Congressman, Jitin Prasada, who was once said to be close to Rahul Gandhi, can be another cause of concern for the Yogi because of the caste factor, which is of prime importance in the Hindi heartland province.

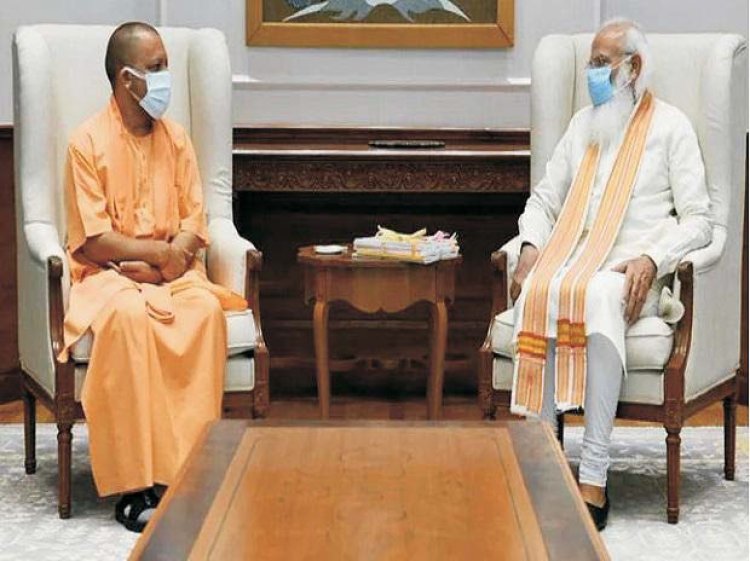

Since Prasada is a Brahmin, he is apparently expected by the BJP to mollify the members of his community, who constitute as much as 13 per cent of U.P.’s population, who are said to be displeased by the chief minister’s tilt towards his own community of the Thakurs. That the Yogi came to Delhi the day after Prasada’s entry to meet Modi and the Union home minister, Amit Shah, who are the Nos 1 and 2 in the BJP’s hierarchy, is deemed significant by political observers. As the Samajwadi Party leader, Akhilesh Yadav, has said, the chief minister is losing control.

Since the Yogi has been one of the star campaigners for the BJP and is sometimes seen by his admirers as Modi’s successor, any reverses which the BJP may suffer in U.P. is bound to be construed as a rejection of not only the chief minister but also of the party’s Hindutva agenda. Unlike Modi and Amit Shah, whose formal commitment is to the sabka saath, sabka vikas slogan of development for all, the Yogi has been quite forthright in his espousal of the Hindu cause, as his categorization of the people into Bajrang Balis and Alis shows.

Although there are still three years to go before the next general election, the BJP will try to ensure that there are no more political road bumps in the intervening period. While success is a must for the party in U.P., it will also expect to fare well in Modi’s and Amit Shah’s home state of Gujarat, especially because it cannot be too sure of performing satisfactorily in Punjab and Goa and perhaps not in Uttarakhand either.

It is not only the election results which will be the BJP’s prime concern. The party will also be aware that its international image has suffered since the early years of Modi’s rule when the world looked up to the new assertive prime minister compared to the outgoing diffident Manmohan Singh. Apart from the pandemic exposing the administrative fault lines, the BJP has also been accused of being intolerant of dissent. Hence, the moniker, “partly free”, by an American think tank, the Freedom House.

Even as the BJP tries to recover its position, Modi’s approval rating has fallen, according to the American data intelligence firm, Morning Consult. Meanwhile, another survey has said that what the people want at present are vaccinations and jobs. After initial hiccups, which made the Supreme Court describe the official vaccination policy as “arbitrary” and “irrational”, the government appears to have got its act together and the earlier sights of people leaving the medical centres because of the shortage of vaccines can no longer be seen.

But even as the situation with regard to vaccines as well as oxygen supply and hospital beds has improved, it is unlikely that the quest of the job-seekers for employment will end any time soon. The BJP will not be too hopeful, therefore, about its prospects as the party’s seventh year in power draws to a close and it enters the eighth year to fight several crucial elections.

The party’s only solace is that in all these contests, its opponents remain weak and disunited. Notwithstanding the satisfactory showing by the Samajwadi Party and the RLD in the U.P. panchayat polls, how effective their cadre base is on the ground is open to question although the restive farmers (who have been agitating for several months) may queer the pitch for the BJP in western U.P. Even then, the BJP’s organizational clout and enormous resources are a huge asset for the party.

In the states outside U.P., the Congress is the BJP’s main adversary. But, except in Punjab, the Congress remains a party in disarray in Gujarat, Goa and elsewhere. Even in Punjab, the infighting in the Congress between chief minister Amrinder Singh and his longstanding bugbear, Navjot Singh Sidhu, can hurt the party although there is no other outfit which can take advantage of the Congress’s troubles since the Akali Dal-BJP combine has fallen apart and the two parties are quite weak by themselves.

It’s a mixed bag, therefore, for the BJP. The party’s easy run of the last seven years when it could have its own way on, say, ending Kashmir’s special status, has ended. But, although it remains a formidable political force, there are dark clouds ahead.