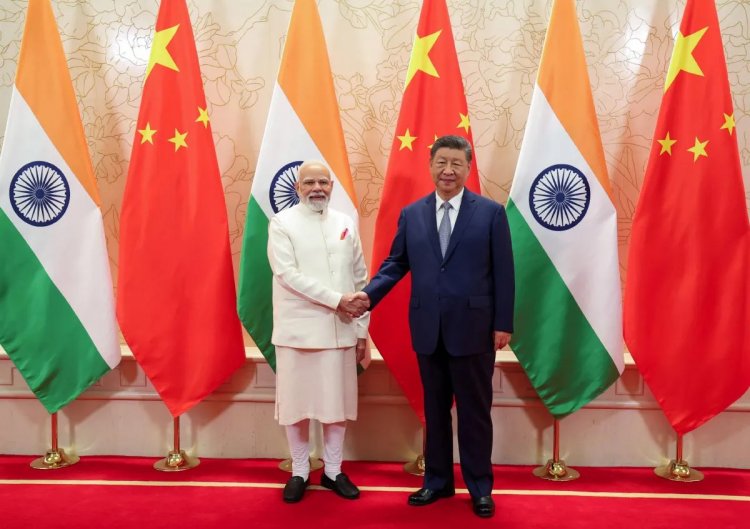

MODI-XI meet reflects a Thaw. But issues that have Bedeviled ties for Decades Remain

STORIES, ANALYSES, EXPERT VIEWS

- Uday Bhaskar

The bilateral meeting between Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping on the sidelines of the SCO summit in Tianjin on Sunday has aroused considerable global interest, given that it took place against the backdrop of unexpected turbulence and discord in India-US bilateral ties, triggered by the petulant weaponisation of trade and tariffs by US President Donald Trump.

The outcome of Tianjin is to be cautiously welcomed. It is a summit-level political endorsement by the two leaders of the broad agreements arrived at during the visit of Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi to Delhi earlier in August. It is instructive that the official statement released by New Delhi referred to both leaders welcoming the “positive momentum and steady progress in bilateral relations since their last meeting” in Kazan, Russia, last year and reaffirming that the two countries were “development partners and not rivals, and that their differences should not turn into disputes.”

This is a familiar template for both Asian giants who have had a troubled and testy relationship since the border war of October 1962 and the most recent military confrontation in Galwan, Ladakh in mid-2020. Subsequently, bilateral ties went into a deep freeze and it took the Kazan meeting for the beginning of a thaw, one that has yielded modest results in Tianjin. A much needed degree of stability, resumption of dialogue and contact at various levels have been restored to the India-China relationship. The resumption of direct flights announced by PM Modi is a tangible outcome as well, although the details have not yet been spelt out.

However, it would be misleading to interpret the Modi-Xi meeting as heralding a breakthrough in the more contentious issues that have bedeviled the relationship for decades. The contested and tangled territorial-cum-border dispute that goes back to the birth of India and China as independent nations (1947 and 1949 respectively) is at the core of the bilateral security dissonance. Repeated attempts at finding a consensual modus vivendi have remained elusive.

In the Tianjin meeting, the two leaders noted “with satisfaction the successful disengagement last year and the maintenance of peace and tranquility along the border areas since then.” Predictably, the old chestnut, “mutually acceptable resolution”, found mention and the statement added that the two leaders “recognised the important decisions taken by the two Special Representatives in their Talks earlier this month, and agreed to further support their efforts.”

In summary, this translates into acknowledging that the border talks will remain a “work in progress” and both countries will seek to engage with each other in other domains. This was reflected in President Xi’s remarks where he noted that the two nations are cooperation partners, not rivals, and that they are each other’s “development opportunities rather than threats.” The much touted and visually rich symbolism of a “cooperative pas de deux of the dragon and the elephant” was also invoked by Xi.

The Tianjin bilateral meeting and the SCO summit that will follow on September 1 are unfolding at a consequential moment in global geopolitics. The American eagle is flapping its wings in an irate manner and the dragon, the elephant and the Russian bear are all differently impacted. Till the draconian Trump tariffs upended the India-US relationship, New Delhi had managed to maintain a delicate balance in its ties with both Washington and Moscow. The anomalous assumption that India could be part of a robust partnership with the US, and an active member of the Quad and still remain invested with Moscow has been belied.

However, it would be misleading to assume that this translates into India joining the China-Russia camp that is ranged against the US. New Delhi has been navigating a carefully calibrated path of not being a camp-follower since 1947, to ensure that its core interests are not adversely impacted. This has often been a lonely furrow to plough. Where and when required, India has stood its ground in a quiet and firm manner when engaging with its principal strategic interlocutors.

India had bitter differences with the US during the Cold War over the NPT (nuclear non-proliferation treaty) and this relationship remained strained from 1974 to 2005. The George Bush-Manmohan Singh rapprochement that led to the Indo-US nuclear deal in 2008 turned the page. The last 17 years have seen a steady consolidation in the India-US partnership. The August 27 imposition of unwarranted tariffs on India by the Trump administration has strained ties but Delhi will have to remain committed to engaging with the US in the long term, given its relevance in the Indian strategic calculus.

China has pursued policies that have been either inimical or adversarial to India’s core interests since 1962, with Beijing aligning itself with the US in the latter part of the Cold War and then with Pakistan. New Delhi has lived with long periods of a breakdown in dialogue and contact with Beijing, going back to the 26-year hiatus that ended in 1988 with the visit of PM Rajiv Gandhi to China.

Beijing was vehemently critical of the Indian nuclear tests of 1998 and sought to play spoiler in the 2008 US-led civilian nuclear accommodation. The 2020 Galwan rupture is now being repaired in Tianjin and the SCO deliberations will testify to the current geopolitical reality: A contra-polar world, where major powers are grappling with complex contradictions.

Modi’s visit to Tokyo prior to Tianjin and the India-Japan joint statement reaffirming “their steadfast commitment to a free and open Indo-Pacific” would have been noted in Beijing and is part of this contra-polar pattern. The tea leaves are muddier than they seem and must be read objectively.

Director, Society for Policy Studies

In association with South Asia Monitor