UP, Punjab, Gujarat Preparing for Polls: Caste and Communal Factors Emerge

STORIES, ANALYSES, EXPERT VIEWS

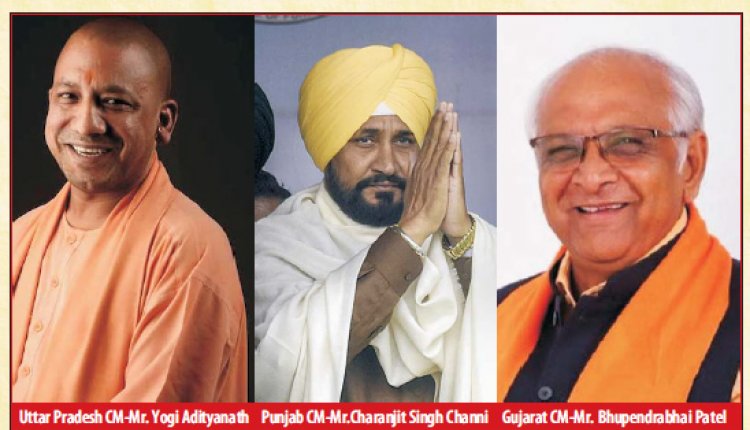

Uttar Pradesh (UP), Punjab and Gujarat have begun preparing for assembly elections that are due early next year. While UP and Gujarat are ruled by the BJP, Punjab is with Congress.

Ministries have been rearranged and rejigged in the first two states, argues The Indian Express “ostensibly for accountability and greater social and regional balance. The exercises in the two states follow the radical revamp the BJP undertook in Gujarat earlier this month, when the entire cabinet, including the chief minister, had to resign. The BJP — in UP and Gujarat — and the Congress — in Punjab — apparently believe that these belated makeovers will help them tide over anti-incumbency and win another term. This speaks of a cynical assumption — that the voters can be fooled through last-minute window-dressing choreographed from Delhi. It also points to a lack of imagination and ideas in the two national parties…..”

In Punjab, the Congress has tried to buy peace among warring factions with a selection of legislators from different camps and regions for the new cabinet. The party also hopes that appointment of a Scheduled Caste Chief Minister, a first for the state, would influence the community — the single largest caste group in Punjab — to consolidate behind it. But such tokenism, as the paper calls it, is unlikely to make a dent on the pressing issues in agriculture, industry, lack of unemployment etc.

In UP, Chief Minister Adityanath “appears to have fallen back on the tested strategy of caste and communal patronage and management. His term so far has been marked by the government’s brutal crackdown on all forms of dissent and a polarising approach to social issues…..”

Political moves involved

In the view of Suhas Palshikar (taught political science and is chief editor of Studies in Indian Politics) the cabinet changes by the BJP and Congress is a reflection on the state of parliamentary democracy. “The message is chillingly pessimistic: They tell us that parties hope to win elections on contingent optics, tentative accommodations and last-minute shows of course correction rather than on the basis of policies, programmes or performance.”

Palshikar identifies some of the nagging issues these political moves involve.

“One such issue is the relation between state units and the central leadership. Both the Congress and BJP have adopted a high command structure of decision making. In the BJP’s case, the authority of the high command stems from its ability to win elections. All office holders are obligated to the high command on account of this……..” The resultant tensions between the “high command and self-made state leaders are bound to become a problem for the party.

“The case of the Congress is more pathetic. The party continues to adopt the formula of ‘high control despite a hollow high command’……..Sonia has lacked the drive and authority of Indira and Rajiv Gandhi. Some leaders enjoyed high status in her name. Rahul Gandhi took the leadership mantle far too seriously and took on regional leaders. Both Sonia and Rahul, because of their limitations, had an excellent opportunity to federalise the party. But they have been inconsistent in their approach and have given mixed signals to ambitious state leaders. Long ago, this caused the exit of Sharad Pawar and Mamata Bannerjee. Rahul seems set on the same path.”

The high command culture, writes Palshikar “brings both the parties almost on par with many state parties that are indispensably dependent on one key leader. Apart from the centralisation of all-India organisations and the inevitable setback to federalisation of working of the party, this has implications for the long-standing issue of intra-party democracy…….In other words, elected members simply do not matter. The erosion of the institution called legislative party, along with the rejection of the cabinet form of government, has produced a monarchical office of the prime minister at the Centre and reduced chief ministers to functionaries occupying office during the pleasure of the party high command.”

Issue of caste dynamics: BJP and Congress to equally blame

Palshikar also flags the issue of caste dynamics. “At one level, both parties seem to have surrendered to the gimmick of caste-based calculations. In each case, a clever caste motif has been invented and advertised……..ushering in a Dalit chief minister (in Punjab) only for five months without a promise of giving the community the leadership of the state in future too, and suddenly engaging with caste arithmetic in a state that is touted as the best-governed state of the country, are all signs of cynical symbolism…….

“Here too, there are striking parallels between the two parties. Both are often confused about the stand to be taken on the caste question. The BJP (the RSS even more so) often decries caste calculations but since his 2014 campaign, Modi has unequivocally advertised that the party cares for the OBCs and that he himself personifies the party’s concern and affection toward the backward classes………The Congress since Rajiv’s time has been at a loss on the caste question and has failed to accommodate the aspirations of backward castes adequately. Now, in addition to the confusion over its Hindu identity, the party seems to have slipped further in the matter of balancing aspirations of various castes and communities.”

Communalism: false narratives on minorities

Apart from caste, there is also the even more serious issue of communalism. In this context, earlier this month, in response to a Right to Information (RTI) query, the Union Home Minister Amit Shah, declared that the perceived threats to the Hindu religion were ‘hypothetical’ and ‘imaginary’.

We can only hope, writes Manoj Joshi (Distinguished Fellow, Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi) “that this response feeds into the current political discourse…….attacks on Muslims are not uncommon these days. Social media and ‘WhatsApp University’ have played a dubious role in spreading fake information. Politicians, ever ready to stir trouble……RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat statement that ‘every Indian citizen is a Hindu’ mean little in the real world………”

Narrative that Hindus will soon be outnumbered by Muslims: One persistent narrative, argues Joshi “suggests that the Hindus will soon be outnumbered by Muslims in the country. The 2011 census says that Muslims constitute 14.2 per cent of the country’s population and this figure is slated to reach around 18.4 per cent by 2050. But by then, the Hindus will constitute 76.7 per cent of the population and Hindu and Muslim population growth rates will be similar.”

A recent Pew Research Centre poll has some answers to this demographic anxiety. It found that India’s religious composition has remained largely stable since Partition and though for years Muslim fertility rates were higher than those of Hindus (a consequence of higher levels of backwardness and illiteracy), they are now more or less converging.

In 2015, the fertility rate for an average Muslim woman was 2.6 and for her Hindu counterpart, it was 2.1. The fertility rate is the average number of babies a woman will have in her lifetime.

A fertility rate of 2.1 means just enough babies will be born to maintain the population levels constant.

Government figures for nine states, released earlier this year, reveal that Hindi-speaking states like Bihar have high fertility rates for people of both religions, while those in Andhra Pradesh, Goa, Himachal Pradesh or Karnataka are below the replacement level for both. The fertility rate in Jammu & Kashmir is 1.45, lower than the fertility rate of Hindus in other states, but ironically, the rate for Hindus in J&K is even lower at 1.32.

Narrative of forced conversions: Another vicious narrative relates to the alleged prevalence of forced conversions. But the real-world data says otherwise. In 2018, an RTI reply in Maharashtra noted that the total number of those who converted in the state in the 43 months studied was 1,687. In a population of around 120 million people, the number is clearly statistically irrelevant, says Joshi. Figures in other states are likely to be similar.

The Pew study cited above surveyed nearly 30,000 Indian adults and found that religious preferences were very stable in the country. As many as 99 per cent of those born Hindu had remained the same into adulthood, while the figures for Muslims and Christians were 97 per cent and 94 per cent, respectively. There were conversions, but Hindus gained as many people as they lost. Yet, there is an enormous din around the need to ban conversions and some nine states have actually passed laws against conversion in recent years.

In democracies, concludes Joshi “it is not unusual for divisions to be accentuated during election time. All parties try and maximise their votes by indirectly and sometimes directly using caste and religion. After the elections, these divisions need to be healed and governance be based on the citizenship of the individual, regardless of caste, creed and gender…….…”

Larger issue of hate

Harsh Mander (Richard von Weizsacker Fellow and a peace and human rights worker and writer) raises a larger issue of hate that is becoming slowly ingrained in society.

“The majority of the Indian people have become so inured to brutal public displays of hate violence that when we consume video images of lynching, gangrape and killing of Dalit women, and the flaunting of bigotry by our leaders, we just turn our faces away. What was it then about the recent images from Darrang in Assam — of a man with a lathi shot in his chest trying to defend his home against hundreds of armed security men, and of a young civilian jumping on and kicking the man’s body even as his last breaths cease — that has stirred public outrage?”

To understand the photographer’s actions, Mander says “we need first to see the dark hole into which we — the people in Assam and rest of India — have fallen. The perversity of hate of the photographer (the civilian), indeed of lynch mobs in many parts of the country, cannot be dismissed as individual social anomalies. These public displays of violent hate targeting India’s Muslims and sometimes Dalits have increasingly become normalised, and public resistance to it is increasingly rare.”