Monsoon, El Nino and MJO Worries

Asia News Agency

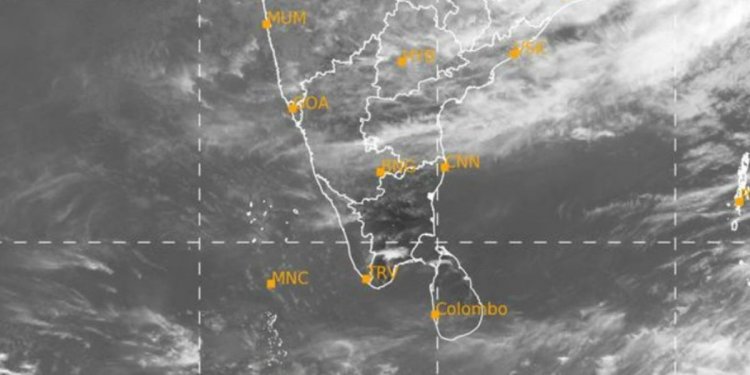

Rainfall in August had been the least in over a century, with India getting 36% less rain than it usually does in the month. August rainfall has been markedly deficient in most of India, except in northeastern India, the Himalayan States, and parts of Tamil Nadu, according to data from the India Meteorological Department (IMD).

The last time India recorded such severe deficits in August was in 2005, when the shortfall was about 25% of the normal, and in 2009, when India saw its biggest drought in half a century and August rainfall was 24% less than what was due.

Rainfall in August has brought the overall, national deficit to 10%, with the regional deficits being 17% in east and northeast India, 10% in central India, and 17% in southern India.

There is a reasonable chance of normal rainfall in September thanks to favourable conditions in the Indian Ocean and two rain-bearing low pressure areas in the Bay of Bengal, getting extra rain is quite difficult

Crop worries

Overall sowing of ‘kharif’ (monsoon) crops, barring pulses, has been satisfactory and higher than last year. But the dry August — and not much of a revival being forecast for the next one week — raises concerns over the crop now in vegetative growth stage.

The real worry, however, writes The Indian Express “may not be with the ‘kharif’ crop — which farmers may be able to salvage with one more shower or even the available moisture. Instead, it would be with the wheat, mustard, onion, potato and other crops to be planted in the upcoming ‘rabi’ (winter crop) season. The Central Water Commission’s latest data on water in 146 major reservoirs show these at 78.6 per cent of last year’s and 93.9 per cent of the 10-year-average levels for this time.”

With El Niño’s effects beginning to show, “there could be pressure on both irrigation reservoirs and groundwater resources that sustain the cultivation of winter-spring crops. That may, in turn, make the current food inflation not just transitory and largely limited to vegetables, but persistent and broad-based….”

That being the case, the government is rightly focussing on supply-side actions.

The MJO, or the Madden Julian Oscillation problem

El Nino is not the only culprit. There's another weather phenomenon called MJO, or the Madden Julian Oscillation. India Meteorological Department (IMD) chief Mrutyunjay Mohapatra said the primary reason for below-normal rainfall in August, besides El Nino was the ‘unfavourable phase of the Madden Julian Oscillation (MJO) which is known to reduce convection in the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea’.

The MJO is an eastward moving disturbance of clouds, rainfall, winds, and pressure that traverses the planet in the tropics and returns to its initial starting point in 30 to 60 days, on average, according to America's National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The MJO consists of two parts, or phases: one is the enhanced rainfall (or convective) phase and the other is the suppressed rainfall phase.

Possible spike in inflation

Normal rainfall is critical for India's agricultural landscape, with 52 per cent of the net cultivated area relying on it. Additionally, it plays a crucial role in replenishing reservoirs essential for drinking water and power generation throughout the country. Rain-fed agriculture contributes to approximately 40 per cent of the country's total food production, making it a vital contributor to India's food security and economic stability.

The summer rainfall deficit could make essentials such as sugar, pulses, rice and vegetables more expensive and lift overall food inflation, which jumped in July to the highest since January 2020. Lower production could also force India, the world's second biggest producer of rice, wheat, and sugar, to impose more curbs on exports of these commodities.

A spike in inflation caused by higher food prices could move the RBI's hand which had paused its rate-hike spree in April. It had raised the repo rate by a total of 250 basis points from May 2022 to February 2023 to control the elevated inflation. Since April, the RBI has maintained the pause but inflation remains a concern. On August 10, the Monetary Policy Committee, the rate-setting panel of the RBI, unanimously voted in favour of a status quo in key rates as inflation shot up above the higher threshold of the tolerance band set for the RBI in July largely due to the spike in tomato prices.

Brokerage HSBC said recently in a note that the central bank would use liquidity management tools as the first line of defence as long as it sees food price pressures arising from just a few items like tomatoes. According to the note, if price pressures around cereal inflation begin to pick up further, then the RBI may be forced to use rate action.

Ultimately, El Nino and MJO might lead to expensive food items and higher interest rates, disrupting household budgets of middle and lower classes.