India’s Continuing Distrust of China

Amulya Ganguli

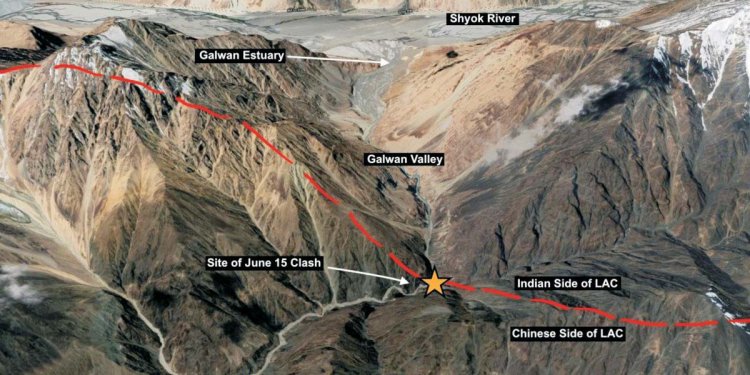

A year after the Sino-Indian skirmish in Galwan in Ladakh, the situation on the border remains as unsettled as before. There may not be a shooting war at present. But peace remains elusive because no disengagement has taken place along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) as might have been expected after 11 rounds of talks between the army commanders of the two sides.

Only in the Pangong Tso area is there a settlement. Otherwise, the situation on the ground remains unresolved in the Hot Springs, Gogra and Depsang areas. As a result, India’s belief that the bilateral relations have been “very significantly damaged” remains a stark reality. Although China is now telling India not to be suspicious of Chinese intentions, thereby allowing differences to become disputes, mistrust continues to be at the root of mutual ties so far as India’s perception is concerned.

Having been betrayed in 1962 when China trashed the Hindi-Chini bhai bhai bonhomie favoured by India by launching a military offensive which saw the Chinese troops come so far into India that there was panic in states like Assam, it is unlikely that misgivings about China’s objectives will disappear in India. Moreover, the distrust has been further fuelled by the Chinese incursions in eastern Ladakh a year ago when India saw no reason why Beijing should want to alter the status quo in the region.

It is only the stout resistance put up by India which seems to have made the Chinese realize that a repeat of 1962 is no longer possible. Hence, its latest friendly overtures which may be due to the President Xi Jinping’s desire to make China “lovable” by the rest of the world. But it will take much more than words to persuade the international community and India to believe that China has had a change of heart.

As of now, the belief remains in India that China will not give up its claims on, say, Arunachal Pradesh, which it regards as southern Tibet, and other areas in Aksai Chin where its troops have entered Indian territory. But since India, too, is unyielding in its refusal to accommodate China in either the eastern or the western Himalayan regions, the standoff between the two nuclear-powered Asian giants is likely to continue in the foreseeable fiuture.

While India has no difficulty in standing firm since it regards the areas claimed by China as its own, the Chinese cannot but be upset both at the thought that they cannot make any headway in achieving its objective of seizing Indian territory and also about the fact that being stalled by India will damage its self-perception of being the No 1 power in Asia which, they believe, is on its way to become the No 1 power in the world as well.

It is the dichotomy between wanting to be loved and wanting to be feared which China is apparently unable to reconcile. Hence, its aggressive acts from South China Sea to the Pamir mountains in Tajikistan and Mt Everest in Nepal which it claims as its own to the bouts with India on the Himalyan heights, not to mention the brutal repression of the Muslim minorities in Xinjiang, the attempt to snuff out Buddhist culture in Tibet and the denial to the people of Hong Kong to live according to the freedoms promised by Beijing in 1997 for half a century during which China is expected to adhere to the “one country, two systems” formula.

At the same time, China is apparently uneasy about being isolated by the other superpower, the US, and its European alles, leaving it in the company of an unstable Pakistan and an Iran which has few friends. While the Sunni Muslim countries of West Asia do not like the Shi’te Iran, Israel is worried about Teheran’s nuclear ambitions. G-7, too, has let it be known at its latest conclave in Britain’s seaside town of Cornwal that it will mostly follow US president Joe Biden’s less than friendly approach towards China.

Even as India ramps up its infrastructure in the north-east with the construction of 12 new strategic routes in Arunachal Pradesh, the two adversaries will be aware of the longstanding nature of the stalemate in their relations. India’s membership of the Quad comprising the US, Australia and Japan, which is ostensibly directed against China, is also bound to give India a sense of confidence in facing its hostile neighbour, an attitude which means that India will not mind a prolonged confrontation.

Given the current impasse, it is clear that there are no clear winners or losers in the present faceoff. Yet, there is little immediate possibility of either side realizing the futility of the continuing deadlock and making the first move to step back to ease the situation. India cannot do so because it is in its own territory. And China will have to weigh the pros and cons of a seeming retreat as it will entail a loss of face for it not only before India but the whole of south-east Asia comprising what China with its medieval Middle Kingdom mentality regards as an area of tributary nations which are expected to kowtow to it.

There is little doubt that its aura of invincibility will go if it is seen to step back. It is not only the “tributary” nations which will be smirking in glee at the humbling of a bully, but the Uighur Muslims, the Tibetans and the people of Hong Kong will be relieved at the chastening of their overbearing lord and master. A year after the Galwan clash where the blood of both Indian and Chinese soldiers were shed, Beijing may well realize that it chewed more than it can swallow in intruding into Ladakh.