Bumpy Road to Peace in Afghanistan

Amulya Ganguli

The looming May 1 deadline of the withdrawal of American troops from Afghanistan appears to have introduced a sense of urgency into the faltering peace process in the war-ravaged country.

The assumption of the US presidency by Joe Biden has also led to India finally finding its place in the peace talks with the Taliban along with the US, Russia, China, Iran and Pakistan. Up until now, India had been kept out on the insistence of Pakistan and its friends like China while others like Donald Trump’s America kept quiet.

Pakistan has always been wary about India playing any kind of a role in Afghanistan, a country which Pakistan thought will provide “strategic depth” in the event of a war with India. This was Pakistan’s calculation when the religious extremists of the Al Qaeda and the Taliban ruled the roost in Afghanistan.

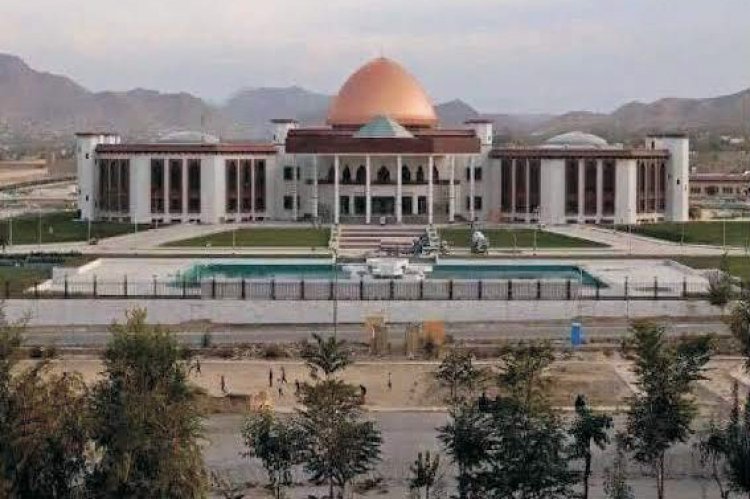

But the scene changed following their defeat by the Americans after 9/11 and India became a close ally of the new Afghan government, building schools, hospitals and even the parliamentary building in 2015, much to Pakistan’s chagrin. All this bonhomie was a reaffirmation of the age-old ties between India and Afghanistan, going back to the ancient times of the Hindu epic, Mahabharata, one of whose main figures, Gandhari, evidently derives her name from the area in Afghanistan now known as Kandahar.

Not surprisingly, during the years of India-Afghanistan friendship, Pakistan virtually became Afghanistan’s sworn enemy, especially for harbouring Osama bin Laden. When the peace talks began, however, between America and the Taliban in Doha and elsewhere, India lost its favoured nation status as none of the negotiators was willing to have it on board except for the friendly Ashraf Ghani government.

The link between New Delhi and Kabul then and now is their mutual dislike of the Taliban. India’s fear is that the Taliban’s reinstatement in Afghanistan will once again turn the benighted country into another epicentre of terror like next-door Pakistan while the Ghani government apprehends that the Taliban will exterminate the moderate Afghan groups and impose its version of the Shariat-based Islamic rule, one of whose main features is the suppression of women.

There is unlikely to be too many moderates in that as well as other parts of the world who will put their faith in an American document, which the US is said to have shared with the Taliban, which guarantees the rights of women and of the religious and ethnic minorities since it also promises to uphold “Islamic values”. The general assumption, therefore, is that the Taliban will scrap the document once the Americans withdraw.

Hence, the Ghani government’s resistance to the terms and conditions being chalked out between the Americans and the Taliban. The Biden administration, however, is resentful of the roadblocks being put up by Kabul since it is stopping the American troops from leaving in a hurry. Having “taken care” of Osama and brought the situation more or less under control (though not fully), the Americans do not want to stay on in a country of which they know little in a far corner of the world.

It is this annoyance which has apparently been conveyed in a strongly-worded letter written by US secretary of state Antony Blinken to the Afghan president, asking him to work collectively with the other Afghan groups, meaning the Taliban, to advance the cause pf peace.

Blinken’s “threat” of a “full withdrawal” of even the 2,500 American soldiers who are still in Afghanistan is reminiscent of Mikhail Gorbachev’s similar missive to the Afghan president, Babrak Karmal, in 1986 on the eve of the Russian withdrawal, telling Karmal that if he wants “to survive, you’ll have to broaden the regime’s social base, forget about socialism and share power”.

Like Ghani today, Karmal, too, resisted listening to his mentor’s advice. But there was no sharing of power as the civil war soon began and has continued, in fits and starts, to this day. For the Taliban, the American withdrawal will be yet another sign of their invincibility, for they can proudly claim to have succeeded in compelling two superpowers to back off even if they could not be defeated in a frontal battle.

Such a turn of events will be a morale booster not only for the Taliban, but for all the jehadis in the region and elsewhere who will be convinced all over again about their righteous cause in fighting the infidels.

In the normal course, India would have been concerned about the reaction of the jehadis in Pakistan and the consequent increase in their violent activity in Kashmir. But the signs of a slight thaw in the India-Pakistan relations following Pakistan army chief, General Qamar Javed Bajwa’s call for peace have put a new spin on the situation.

It is just possible that Pakistan will rein in the militants and not let them run amok in Kashmir. If that happens, the American withdrawal from Afghanistan will not be fraught with fateful consequences for India as New Delhi fears.

But even if India is spared the kind of mayhem which the Pakistani infiltrators tend to perpetrate, Afghanistan may not be able to enjoy such a reprieve from acts of violence against a “secular” authority by the Taliban.

Even if the Taliban in the main abides by an agreement to let women go to educational institutions or allow a “free press” to function, there are still bound to be groups which will not accept diktats which go against their core beliefs. The hope, therefore, of peace returning to the land is a dim one.